The human hand is comprised of 27 bones, 29 joints, at least 123 named ligaments – and has countless uses. Our hands are a structure not only of great complexity, but also of tremendous utility. Think of how much you can accomplish by using them. Whether striving to achieve success as an architect, a musician, a doctor, or a laborer, your hands are a conduit for achieving both short and long term successes. They also give each of us a unique imprint for identification and can be a window into ailments such as vitamin deficiency, anemia, and chronic or acute pulmonary disorders. An injury to this vital structure has the potential for devastating consequences if not treated by another’s set of gifted counterparts.

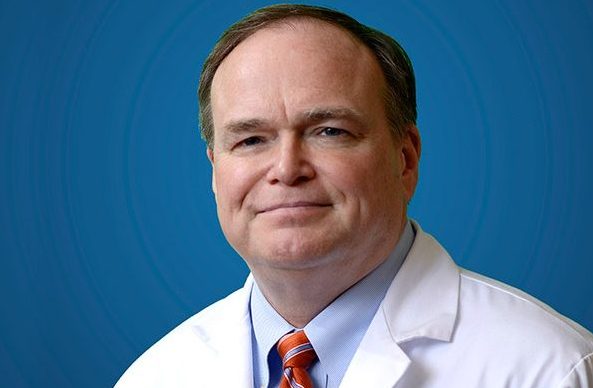

We sat down with Dr. Robert Hotchkiss, a renowned hand surgeon at the Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) in New York City, to learn a bit more about his professional journey and aspirations for the future of orthopedics. At HSS, Dr. Hotchkiss is the Anne and Joel Ehrenkranz Chair of Hand and Upper Limb Research, Medical Director of Innovation, and Medical Director of Clinical Research. He has treated many patients who rely on their hands and upper extremities for personal and professional success. Dr. Hotchkiss is also a member of the Summus Medical Advisory Board.

Jennifer Kherani: You have had a successful and distinguished career. How did you decide upon your chosen career and specialty?

Robert Hotchkiss: It was really a process of elimination. I am a procrastinator and much of my career path has been serendipity and happenstance. In college, I thought I was to become a chemist and, in that day and age, that meant you needed to know German or Russian. I chose to double major in Chemistry and Slavic Languages. I traveled to Leningrad amidst the Cold War to enrich my education, but ultimately found that the life of a chemist was a lonely one. I returned to the U.S. and decided upon medical school. While there, I enjoyed Endocrinology and Psychiatry but my mentor noted that I seemed to truly enjoy surgery. He was right. I thought I would end up in spine surgery but, again, made a late decision on fellowship and somewhat randomly landed in a hand fellowship. I loved the technical difficulty and challenge I found. It led me to HSS where I have pretty much been evolving my career ever since.

JK: Some of the most famous hands in the world have put their trust in yours. What lessons have you learned, and do you find it to be more stressful when your patient is relying on your outcome for the future success of their (well known) career?

RH: I often treat patients who are well known actors, athletes and musicians. They have many choices and their greatest challenge is to find someone whom they can trust. Fame can naturally create an air of distrust. Many of them actually have less complex injuries and “easier” cases. I also see “normal” individuals who have far more complicated surgical needs. Famous individuals certainly have perceived higher stakes, but honestly my intensity doesn’t change between patients. It all depends on the clinical challenge.

JK: What has been your most challenging case and why?

RH: I don’t really think in terms of cases but rather concepts. There are difficulties that arise such as nerves buried into bone, as I saw in a young man with an upper extremity fracture at a young age, or having to rebuild blood vessels, recover nerves and create muscle and tissue flaps, as I did in the case of a 7 year old girl who had sustained a severe equine injury. However, it’s concepts such as friction that lead me to really deliberate a solution. There is also a difficulty to the psychology of cure. Our hands are as essential to our social communication as our faces. Think about it, the first thing we do upon meeting someone is extend a hand. Choosing between amputation and deformity or how to salvage certain functionality is a tremendous challenge for me as well as the patient.

JK: What would be your advice to a patient with a hand injury choosing a physician?

RH: In choosing doctors, you have to ask if there are metrics or surrogacy for quality. You have to gain confidence without the benefit of months of observing that individual at work. Look at the institution first. It’s not 100% but it certainly provides the first layer of trust. Also read about what that person has spent their career doing. Who do they operate on? What types of procedures do they do and in what volume? Do they investigate? Innovate? Those concepts are usually based on problem-solving. Writing a great paper does not make you a great surgeon, but it’s a start. That person is on a quest to solve a problem and has been gaining naturally motivated experience in doing so.

JK: You were recently named the first ever Chief Innovation Officer at HSS to identify and support the next generation of cutting-edge medicine and science technology. Is the purpose of the role to improve clinical outcomes? What is the next promising concept in orthopedics?

RH: Yes, that’s correct. Translational medicine is kind of a buzz word. It’s designed to take the benchtop to the bed side. Our goal is to create an environment where ideas for discovery can become functional. We want to create an incubator of sorts which can translate ideas into products such as devices, drugs or treatment algorithms in order to more rapidly and effectively benefit patients in a tangible way. Navigating things such as patent applications, FDA regulations, and experimental set-up all take time and manpower. If we have a system to guide our investigators, they can focus on their work. I think that the next great advancement is a smart technology combination rather than an entirely new product. When we combine new methods of manufacturing, specifically additive manufacturing of things like biocompatible titanium, and new wave imaging, like creating computational models, it will allow us to do incredible things. This combination will increase our understanding of local delivery, such as drugs and implant coating, and out of that stew will be significant advancements. We’ll be better able to understand difficult concepts and injuries and overcome them by learning more before we approach the patient. We’ll improve mobility and get people walking again faster and more effectively.